and ones that are more connected to my visceral reading experience, a lovelorn fan attachment. So I’m sure I am not alone in being a little nervous around these rumors (although the one about a feature film with Clive Owen is certainly intriguing).

and ones that are more connected to my visceral reading experience, a lovelorn fan attachment. So I’m sure I am not alone in being a little nervous around these rumors (although the one about a feature film with Clive Owen is certainly intriguing).In general, I feel the most promising prospect for a new effort to bring Marlowe to screens large or small would be neither to update him and plug him into yet another crime show, nor to keep him cloaked forever in bland retro stylings. Instead, I’d suggest (and I’m sure I’m not the first to do so) taking a cue from the forces behind 2006’s Casino Royale.

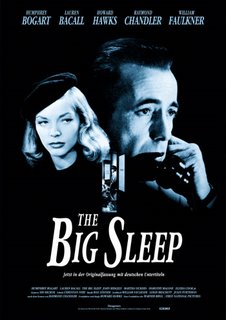

The still-strong cultural association between Humphrey Bogart (The Big Sleep) and Philip Marlowe is comparable to that of Sean Connery and James Bond. The weight of the iconic rendering in both cases--with the addition of just plain series-exhaustion in the latter--eventually brought both characters into the realm of parody. But Casino Royale, both via the performance of Daniel Craig and the 2006 film’s approach to its source text, blew the cobwebs off the whole nostalgia-drenched contraption. Could a similar approach work for Raymond Chandler’s Marlowe?

The Bond we see in Casino Royale throws us headlong back into the Bond of the early Fleming novels, where we found a man of staggering nastiness (the opening restroom scene is a winner), un-slicked-over, un-ironized. We also see his chilly remoteness, which just barely conceals both a fear of vulnerability and a desire to render himself vulnerable (and then regret it). There’s an emotional complexity, and a tendency toward masochism, that is unexpected and riveting, just as it is in the book. Craig, in his performance, threads these dark strands through every scene. It’s Bond as a cold, dangerous, difficult man who is, to be melodramatic about it, slowly learning to seal off his heart.

Echoes of Marlowe here, to be sure, although Marlowe’s warmth and humor are among his most conscious attributes. (It’s interesting to recall that Fleming and Chandler were friends, with Fleming a great admirer of Chandler and Chandler a great supporter of Fleming and his work, especially Casino Royale.) Yet the point is not the similarity between Marlowe and Bond, but the pleasures to be gained by returning to the source text and reaching for the elements of the original character that may have been lost in these many decades of flattening out, tarting up, and otherwise stripping these iconic figures of all that is unexpected in them.

In the case of Marlowe, especially at his most nerve-addled and fraught, heartbroken and reeling (such as at the hands of Terry Lennox in The Long Goodbye), there is so much richness that has gone unexplored in TV and film renderings. We’ve seen good and fair Marlowes, nostalgic and ironic Marlowes, but what would it be like to see a Marlowe who is capable of a dark and haunting conversation with a docks tramp about his fear of death (Farewell, My Lovely)? Or a Marlowe who, after killing a thug (in The Big Sleep), begins to “laugh like a loon” and can’t control himself until, suddenly, he stops as quickly as he started?

Wouldn’t that be something to see?

5 comments:

I wonder also whether it would be possible to recapture the raciness of the Bogart-Bacall nightclub conversation in The Big Sleep.

Marlowe's encounter with General Sternwood in the hothouse has an interesting echo in The Dying Trade by the Australian writer Peter Corris.

Peter

===================

Detectives Beyond Borders

"Because Murder Is More Fun Away From Home"

http://www.detectivesbeyondborders.blogspot.com/

Didn't Altman do exactly this? He rendered the Marlowe image to the early seventies. I still don't know what was so wrong about this, even though I must admit that I'd have hard time to see Marlowe with a cell phone. It would be interesting, but I'd like to see the remodeling still taking place in the 1940's and 1950's Los Angeles. Those were dark times, as everyone who's read Ellroy knows. (And clearly Megan Abbott, but I'm sorry to say that I haven't as yet had the opportunity to read her work. Thanks for very interesting posts here, though!)

Hi, Juri!

I'd say that Altman's rendering had far more to do with a desire to take aim at the mythic Marlowe that emerged in the 1950s and on, steeped in nostalgia and trapped in cliche, a Marlowe that owes far more of a debt to the Bogart rendering than the books. And Altman expertly skewered THAT Marlowe. But, for me, the Marlowe of the books has much more ambiguity and sorrow at his core, much more self-doubt and dark places... and that's a Marlowe I'd love to see.

Oh, yes, David! And that's another element that's been, by and large, lost over the years in representations of Marlowe: the class complications that rustle and swell continuously through the books (all the more interesting, given Chandler's own years in the oil industry). And I think the danger of episodic television for Chandler would be the impulse toward far more coherent plotting, as it's hard to find a *network* TV show that doesn't value organized plots, wrapping up loose ends, etc.

Yes, Megan, you're right about Altman, Gould and Bogart. And yes, there hasn't been any Chandler film version to really appreciate his critique of the society.

Post a Comment