Showing posts with label Jim Thompson. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Jim Thompson. Show all posts

Monday, November 10, 2014

“She Was Giving Me the Kind of Look

I Could Feel in My Hip Pocket”

I’d forgotten until today that Jim Thompson--yes, that Jim Thompson, the author of such hard-boiled classics as The Killer Inside Me (1952), The Criminal (1953), and The Grifters (1963)--made a cameo appearance in the 1975 film Farewell, My Lovely, adapted from Raymond Chandler’s 1940 novel of the same name and starring Robert Mitchum as private investigator Philip Marlowe. According to the Internet Movie Database (IMDb), this was Thompson’s only acting job, though he’d penned episodes of the TV series Cain’s Hundred and Dr. Kildare, and several of his novels were made into movies.

In the video clip embedded above, Thompson, then in his late 60s (he died in 1977 at age 70), plays Judge Baxter Wilson Grayle, said to be “the most powerful political figure in Los Angeles.” Perhaps the reason I forgot he was even in the picture (saying very little, it should be added) is because this scene is more than slightly dominated by Charlotte Rampling, as Helen Grayle, his seductive and much younger wife (she was then only 29 years old), who makes a pretty obvious but potent play for Marlowe’s affections. How the old gumshoe resisted her charms is beyond me.

READ MORE: “Marlowe Goes to the Movies,” by J. Kingston Pierce

(The Rap Sheet).

Labels:

Jim Thompson,

Raymond Chandler,

Videos

Wednesday, August 04, 2010

Lives on the Edge

There’s a great wave of international crime films--Red Riding, Farewell, A Prophet, the upcoming Animal Kingdom, not to mention that picture about the girl who did that thing one time (like nobody’s made that joke before)--making the rounds this year.  But even amidst one of the worst summers ever for mainstream movies, you can still find a couple of features worth your time. One might be the best American film of the year; the other is just OK, yet still worth a look.

But even amidst one of the worst summers ever for mainstream movies, you can still find a couple of features worth your time. One might be the best American film of the year; the other is just OK, yet still worth a look.

The Sundance Grand Jury Prize: Dramatic Film winner, Winter’s Bone, is the aforementioned “possible best American film of the year” (at least until The Town comes out this fall). Based on the novel of the same name by Daniel Woodrell, this picture finds 17-year-old Ree Dolly (Jennifer Lawrence) tracking her missing meth-dealer father through the Missouri Ozarks after the man puts their house up for bond without her knowledge. Described as “hillbilly noir” or “Ozarks noir,” the movie weaves noir tropes with simple, breathtaking scenes of life in an economically depressed region. Working with cinematographer Michael McDonough, director Debra Granik has created a beautiful-looking film that reminded me more than once of the communities in the Catskills where I lived for a time, or of the summer I spent in West Virginia.

Anyone who’s seen the kind of poverty depicted here will be moved by both the details and the film’s overall tone. A scene in which Ree investigates a burned-out meth lab gets equal time to one that finds Ree teaching her siblings how to hunt squirrels. Plot lies buried in scenes of people just scraping by, offering each other food or care--a care that extends to even the movie’s most horrifying moments. The film moves at a elegiac yet brisk pace, and when the story explodes in violence, it doesn’t feel unjustified.

More than the technical aspects of Winter’s Bone, what makes this film a must-see are the performances. It’s a motion picture about people living both in and out our time--the meth of the plot could just as easily have been moonshine--but Granik never makes her characters caricatures. Everyone in the cast appears authentic and lived-in; Granik used non-actors and locals in a few roles, which pays off wonderfully. There’s haunting weariness in these folks’ eyes and in their faces that lends the film an added authenticity. But it is actors Jennifer Lawrence and John Hawkes (playing Ree’s uncle, Teardrop) who anchor the film. Their work here is the best reason to watch Winter’s Bone. Yes, even more than to see legendary Garret Dillahunt as the local sheriff.

Lawrence is the Carey Mulligan (An Education) of 2010, a young actress delivering a subtle performance that refuses to make obvious choices. Ree Dolly could easily have been a stereotypical “tough chick” in the Lisbeth Salander mold; but instead Lawrence imbues her with a fear and naïveté that sells the performance. While Ree’s got a smart mouth like the great noir heroes, the fact that she’s a teenage girl adds another layer of menace to scenes in which she’s facing a roomful of bearded giants. Lawrence never lets you forget who Ree is--or who Ree wants to be, or thinks she already is--and it makes you root for her even more.

There’s already Oscar talk for Jennifer Lawrence’s performance and the film itself, and while both are deserving, I’d really like John Hawkes to pull a nomination for Best Supporting Actor. Hawkes is best known for his work as Sol Star on the HBO-TV series Deadwood, but I remember him too as the convenience-store clerk in From Dusk Till Dawn (he never said “help us!”) and Kenny Powers’ brother on Eastbound and Down. Those quiet, sometimes goofy roles were Hawkes’ bread and butter for a long time, which is why his performance as Uncle Teardrop--a convict looking out for himself until he can’t live with himself any longer--knocked me on my ass. He fills the role with a ferocity that I didn’t know he was capable of--and I love it when an actor can surprise me like that. Teardrop is a tough character. I’ve read comparisons to Omar Little from The Wire, and find them apt. Teardrop is a figure other characters are afraid of, and even though we don’t see much of his fearsomeness on-screen, Hawkes makes you believe it with his stillness and his posture and his eyes of pure steel. This is a man who has seen things, and that attitude carries over into the quiet moments as well. Weeks after watching Winter’s Bone, Hawkes’ final line stays with me, and I hope this leads to more work for him--because, gosh, he’s so good.

Not as first-rate as Jennifer Lawrence or John Hawkes is Bill Pullman in The Killer Inside Me. In fact, this onetime president of the United States isn’t very good at all, giving a ranting and raving performance as West Texas lawman Lou Ford’s lawyer only in a couple of scenes at the end of the picture. But if his acting isn’t the reason to see The Killer Inside Me, director Michael Winterbottom’s adaptation of the famous 1952 novel of that same name by Jim Thompson, it’s certainly one of them, if only because it left me wondering, Was Pullman bad, or did he loop around to being so bad, it’s good? I opted for the latter.

Fortunately, the film isn’t as bad on the whole as Pullman’s role in it. Too flawed to be a classic but strong enough to avoid a one-way trip on the failboat, Killer is, like Winter’s Bone, a movie that arrives from Sundance surrounded by much buzz. Or, in this case, much controversy over its graphic violence and nihilistic tone. Despite James Ellroy and serial-killer documentaries on A&E-TV being my gateway drug to the world of crime fiction, I’m a pretty squeamish guy--which is a long-winded way of saying that I thought the violence was shocking, but nowhere near as shocking as I had heard before seeing the movie.

Killer’s impact comes from Winterbottom’s tight cinematic focus on Deputy Sheriff Lou Ford (Casey Affleck). Sometimes he allows Ford to hold our attention a little too long, long enough for the character to really get under your skin. For me, the two most frightening moments in this movie involve Ford’s face. In one case, the deputy gleefully describes a murder he’s committed, while in the other he looks on as one of his victims dies, Ford’s visage cold and utterly lifeless.

this movie involve Ford’s face. In one case, the deputy gleefully describes a murder he’s committed, while in the other he looks on as one of his victims dies, Ford’s visage cold and utterly lifeless.

In the annals of modern crime fiction, Lou Ford is a more iconic character than Patrick Kenzie in Gone, Baby, Gone and less iconic than Robert Ford (no relation) in The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford. Of the three Affleck performances, however, I like this one more than I did his Robert Ford but not as much as his Patrick Kenzie. Lou Ford could easily be Patrick Bateman (American Psycho) in 1950s Texas, educating hooker Jessica Alba on the merits of Bob Willis and the Texas Playboys. Instead, Affleck chooses to be an “aw-shucks, ma’am” sociopath, going about his life as a small-town lawman until an encounter with Alba leads him into an S&M affair and a revenge scheme. It’s never about money for Ford, though--he’s in it for the fun of tweaking people he knows he’s smarter than, and thinks he’s better than.

That approach, reminiscent of charming serial killers such as Ted Bundy, whose reign of terror was still on the horizon back in the ’50s, makes The Killer Inside Me a companion piece to 2007’s No Country for Old Men, especially when it comes to law-enforcement’s response to Lou Ford’s violent deeds. (Consider why Ford’s boss does what he does.) Thankfully, this film never asks you to empathize with the serial killer, even when you’re presented with the reasons why he might behave the way he does.

Affleck, like Lawrence in Winter’s Bone, is supported in this picture by a rock-solid cast--excepting, of course, the aforementioned Mr. Pullman. Ned Beatty, Simon Baker, and Elias Koteas all do solid work, as do Jessica Alba and Kate Hudson. Hudson, as the woman who loves Ford without actually knowing him, is the standout among the supporting players; this was my favorite presentation of hers since Almost Famous (2000). She delivers a very adult performance that takes her to some dark places, and I hope we see more work like this from Hudson in the future.

Despite its strengths and the fact that it is a period offering that doesn’t feel like one, The Killer Inside Me has problems, though not enough to prevent me from recommending it to other moviegoers. It’s never clear whether we’re watching actual events, Ford’s interpretation of those events, or both at the same time; and the plot that wraps around those actions can be hard to follow at times. I’m a big fan of ambiguity in film endings, but not unearned ambiguity. And while the last act or so of this movie seems like Winterbottom is having fun with the genre à la his earlier films Tristram Shandy (aka A Cock and Bull Story) and 24 Hour Party People, the fact that he doesn’t make that clear left me scratching my head over the apocalyptic note on which The Killer Inside Me ends--and not in a good way.

Just like Bill Pullman. Because really, what was he doing here?

The Killer Inside Me and Winter’s Bone are both good alternatives to the summer doldrums, and proof that the indie film industry in America is far from dead. They’re also nice reminders that, during this new wave of international crime flicks, those of us in the States can still produce a pretty damn good crime picture from time to time.

But even amidst one of the worst summers ever for mainstream movies, you can still find a couple of features worth your time. One might be the best American film of the year; the other is just OK, yet still worth a look.

But even amidst one of the worst summers ever for mainstream movies, you can still find a couple of features worth your time. One might be the best American film of the year; the other is just OK, yet still worth a look.The Sundance Grand Jury Prize: Dramatic Film winner, Winter’s Bone, is the aforementioned “possible best American film of the year” (at least until The Town comes out this fall). Based on the novel of the same name by Daniel Woodrell, this picture finds 17-year-old Ree Dolly (Jennifer Lawrence) tracking her missing meth-dealer father through the Missouri Ozarks after the man puts their house up for bond without her knowledge. Described as “hillbilly noir” or “Ozarks noir,” the movie weaves noir tropes with simple, breathtaking scenes of life in an economically depressed region. Working with cinematographer Michael McDonough, director Debra Granik has created a beautiful-looking film that reminded me more than once of the communities in the Catskills where I lived for a time, or of the summer I spent in West Virginia.

Anyone who’s seen the kind of poverty depicted here will be moved by both the details and the film’s overall tone. A scene in which Ree investigates a burned-out meth lab gets equal time to one that finds Ree teaching her siblings how to hunt squirrels. Plot lies buried in scenes of people just scraping by, offering each other food or care--a care that extends to even the movie’s most horrifying moments. The film moves at a elegiac yet brisk pace, and when the story explodes in violence, it doesn’t feel unjustified.

More than the technical aspects of Winter’s Bone, what makes this film a must-see are the performances. It’s a motion picture about people living both in and out our time--the meth of the plot could just as easily have been moonshine--but Granik never makes her characters caricatures. Everyone in the cast appears authentic and lived-in; Granik used non-actors and locals in a few roles, which pays off wonderfully. There’s haunting weariness in these folks’ eyes and in their faces that lends the film an added authenticity. But it is actors Jennifer Lawrence and John Hawkes (playing Ree’s uncle, Teardrop) who anchor the film. Their work here is the best reason to watch Winter’s Bone. Yes, even more than to see legendary Garret Dillahunt as the local sheriff.

Lawrence is the Carey Mulligan (An Education) of 2010, a young actress delivering a subtle performance that refuses to make obvious choices. Ree Dolly could easily have been a stereotypical “tough chick” in the Lisbeth Salander mold; but instead Lawrence imbues her with a fear and naïveté that sells the performance. While Ree’s got a smart mouth like the great noir heroes, the fact that she’s a teenage girl adds another layer of menace to scenes in which she’s facing a roomful of bearded giants. Lawrence never lets you forget who Ree is--or who Ree wants to be, or thinks she already is--and it makes you root for her even more.

There’s already Oscar talk for Jennifer Lawrence’s performance and the film itself, and while both are deserving, I’d really like John Hawkes to pull a nomination for Best Supporting Actor. Hawkes is best known for his work as Sol Star on the HBO-TV series Deadwood, but I remember him too as the convenience-store clerk in From Dusk Till Dawn (he never said “help us!”) and Kenny Powers’ brother on Eastbound and Down. Those quiet, sometimes goofy roles were Hawkes’ bread and butter for a long time, which is why his performance as Uncle Teardrop--a convict looking out for himself until he can’t live with himself any longer--knocked me on my ass. He fills the role with a ferocity that I didn’t know he was capable of--and I love it when an actor can surprise me like that. Teardrop is a tough character. I’ve read comparisons to Omar Little from The Wire, and find them apt. Teardrop is a figure other characters are afraid of, and even though we don’t see much of his fearsomeness on-screen, Hawkes makes you believe it with his stillness and his posture and his eyes of pure steel. This is a man who has seen things, and that attitude carries over into the quiet moments as well. Weeks after watching Winter’s Bone, Hawkes’ final line stays with me, and I hope this leads to more work for him--because, gosh, he’s so good.

Not as first-rate as Jennifer Lawrence or John Hawkes is Bill Pullman in The Killer Inside Me. In fact, this onetime president of the United States isn’t very good at all, giving a ranting and raving performance as West Texas lawman Lou Ford’s lawyer only in a couple of scenes at the end of the picture. But if his acting isn’t the reason to see The Killer Inside Me, director Michael Winterbottom’s adaptation of the famous 1952 novel of that same name by Jim Thompson, it’s certainly one of them, if only because it left me wondering, Was Pullman bad, or did he loop around to being so bad, it’s good? I opted for the latter.

Fortunately, the film isn’t as bad on the whole as Pullman’s role in it. Too flawed to be a classic but strong enough to avoid a one-way trip on the failboat, Killer is, like Winter’s Bone, a movie that arrives from Sundance surrounded by much buzz. Or, in this case, much controversy over its graphic violence and nihilistic tone. Despite James Ellroy and serial-killer documentaries on A&E-TV being my gateway drug to the world of crime fiction, I’m a pretty squeamish guy--which is a long-winded way of saying that I thought the violence was shocking, but nowhere near as shocking as I had heard before seeing the movie.

Killer’s impact comes from Winterbottom’s tight cinematic focus on Deputy Sheriff Lou Ford (Casey Affleck). Sometimes he allows Ford to hold our attention a little too long, long enough for the character to really get under your skin. For me, the two most frightening moments in

this movie involve Ford’s face. In one case, the deputy gleefully describes a murder he’s committed, while in the other he looks on as one of his victims dies, Ford’s visage cold and utterly lifeless.

this movie involve Ford’s face. In one case, the deputy gleefully describes a murder he’s committed, while in the other he looks on as one of his victims dies, Ford’s visage cold and utterly lifeless.In the annals of modern crime fiction, Lou Ford is a more iconic character than Patrick Kenzie in Gone, Baby, Gone and less iconic than Robert Ford (no relation) in The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford. Of the three Affleck performances, however, I like this one more than I did his Robert Ford but not as much as his Patrick Kenzie. Lou Ford could easily be Patrick Bateman (American Psycho) in 1950s Texas, educating hooker Jessica Alba on the merits of Bob Willis and the Texas Playboys. Instead, Affleck chooses to be an “aw-shucks, ma’am” sociopath, going about his life as a small-town lawman until an encounter with Alba leads him into an S&M affair and a revenge scheme. It’s never about money for Ford, though--he’s in it for the fun of tweaking people he knows he’s smarter than, and thinks he’s better than.

That approach, reminiscent of charming serial killers such as Ted Bundy, whose reign of terror was still on the horizon back in the ’50s, makes The Killer Inside Me a companion piece to 2007’s No Country for Old Men, especially when it comes to law-enforcement’s response to Lou Ford’s violent deeds. (Consider why Ford’s boss does what he does.) Thankfully, this film never asks you to empathize with the serial killer, even when you’re presented with the reasons why he might behave the way he does.

Affleck, like Lawrence in Winter’s Bone, is supported in this picture by a rock-solid cast--excepting, of course, the aforementioned Mr. Pullman. Ned Beatty, Simon Baker, and Elias Koteas all do solid work, as do Jessica Alba and Kate Hudson. Hudson, as the woman who loves Ford without actually knowing him, is the standout among the supporting players; this was my favorite presentation of hers since Almost Famous (2000). She delivers a very adult performance that takes her to some dark places, and I hope we see more work like this from Hudson in the future.

Despite its strengths and the fact that it is a period offering that doesn’t feel like one, The Killer Inside Me has problems, though not enough to prevent me from recommending it to other moviegoers. It’s never clear whether we’re watching actual events, Ford’s interpretation of those events, or both at the same time; and the plot that wraps around those actions can be hard to follow at times. I’m a big fan of ambiguity in film endings, but not unearned ambiguity. And while the last act or so of this movie seems like Winterbottom is having fun with the genre à la his earlier films Tristram Shandy (aka A Cock and Bull Story) and 24 Hour Party People, the fact that he doesn’t make that clear left me scratching my head over the apocalyptic note on which The Killer Inside Me ends--and not in a good way.

Just like Bill Pullman. Because really, what was he doing here?

The Killer Inside Me and Winter’s Bone are both good alternatives to the summer doldrums, and proof that the indie film industry in America is far from dead. They’re also nice reminders that, during this new wave of international crime flicks, those of us in the States can still produce a pretty damn good crime picture from time to time.

Labels:

Daniel Woodrell,

Jim Thompson

Friday, July 03, 2009

The Book You Have to Read:

“The Criminal,” by Jim Thompson

(Editor’s note: This is the 55th installment of our Friday blog series highlighting great but forgotten books. Today’s choice comes from Nate Flexer, author of The Disassembled Man,  an “unrelentingly dark” new psycho noir novel from New Pulp Press. Flexer is the pseudonym of New Pulp proprietor Jon Basoff.)

an “unrelentingly dark” new psycho noir novel from New Pulp Press. Flexer is the pseudonym of New Pulp proprietor Jon Basoff.)

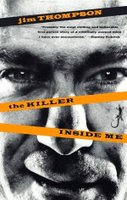

With sleazy cover art and over-the-top titles, Jim Thompson’s books often appeared indistinguishable from all the other cheap paperbacks being churned out in the 1950s by publishers such as Gold Medal and Lion Books. But Thompson, nicknamed the “Dimestore Dostoyevsky,” created some of the most poignant literature of the 20th century. Employing unreliable narrators, a wicked sense of humor, and surrealistic imagery, Thompson helped transform the derided pulp genre into art. His most well-regarded works--The Killer Inside Me (1952), Savage Night (1953), A Hell of a Woman (1954), and Pop. 1280 (1964)--all used the disconcerting technique of casting madmen to narrate his tales (filmmaker Stanley Kubrick called The Killer Inside Me “probably the most chilling and believable first-person story of a criminally warped mind I have ever encountered.”). But it was a little-known 1953 novel called The Criminal that perhaps best showed Thompson’s concern for the disintegration of our collective morality.

The Criminal centers around the heinous murder and rape of a teenage girl named Josie Eddleman. Almost immediately, suspicion surrounds Bob Talbert, a teenage neighbor of the victim and the last person to see her alive. But as the novel weaves towards its ambiguous ending, Bob’s guilt or innocence becomes largely irrelevant. No, the audience never does find out if Bob Talbert is guilty of rape or homicide--although he is certainly guilty of something. But then again, every character in this novel is guilty of something. In fact, despite its title, this book is more a study of the jury than the criminal, a study of collective guilt.

One of the more fascinating elements of Thompson’s writing was his constant experimentation with narration. Unlike most pulp novelists, Thompson eschewed a straightforward telling of his yarns, instead creating narrators who are extraordinary for their unreliability. While Thompson was a gifted storyteller, his major strength comes from his psychological portraits. Motives are rarely what they appear to be. Rare, too, is the character in a Thompson novel who has a moral center; rather, we see men and women who are overwhelmed by their own devious thoughts and uncontrolled passions. In The Criminal, Thompson provides not one, but nine different voices. Each of those voices has his/her own version of the truth, but we as readers soon find it apparent that none of those voices really provides the truth, that perhaps there is no single truth, at least not one without prejudice. It is important to note that Jim Thompson was heavily influenced by William Faulkner, and The Criminal certainly has echoes of Faulkner’s Southern Gothic masterpiece, As I Lay Dying (1930), both in terms of theme and narrative technique. And while perhaps The Criminal doesn’t match the narrative genius of As I Lay Dying, it comes mighty close. Thompson lacked Faulkner’s lyricism and uncanny sense of place, but he matched Faulkner in terms of dark humor and social understanding.

Before Thompson became a fiction writer, he was a journalist, and he shows a healthy amount of cynicism for the profession and how the media can create an alternative reality. The newspaper reporter in this novel, a man named Bill Willis, is able to manipulate the public into figuratively crucifying Bob before any evidence is actually presented. Because Bob is known as a sub-par student and all-around slacker, Willis is able to feast upon the public’s tendency to stereotype, and turn a truant into a murderer.

While The Criminal doesn’t contain the spectacular brutality of some of Thompson’s other works, there is a kind of weary resignation evident throughout its pages. Early in the book, Bob’s father says: “You just rock along, doing the things that you have to, and you get kind of startled sometimes when you stand off and look at yourself. You think, my God, that isn’t me. How did I ever get like that? But you go right ahead, startled or not, hating it or not, because you don’t actually have much to say about it. You’re not moving so much as you are being moved.” And later the D.A’s wife muses: “Isn’t it terrible? You’re just like you always were, the very same person, and suddenly that isn’t good enough anymore.”

Some readers may find the ending of The Criminal a bit disappointing, since there is no tidy resolution. However, that ambiguity is exactly what makes the novel powerful. As the story progresses, we can’t help but sympathize with this boy who has been charged with the crime. In fact, when we actually hear from Bob, he comes across as an upstanding young man and a sympathetic character. But Thompson was fascinated by the sociopaths and their ability to make people believe that they are something other than what they really are. For those of us who read The Killer Inside Me and Pop. 1280, we can’t help but wonder if Bob is, in fact, pulling the wool over our eyes.

In the end, the town and tabloids forget about Josie Eddleman, and Bob Talbert’s guilt or innocence becomes largely irrelevant. Ultimately, all that we are left with is a smörgåsbord of greed and betrayal, creating a Thompsonian view of a universe drenched with moral nihilism.

READ MORE: “The Book You Have to Read: The Grifters, by Jim Thompson,” by Chris Knopf (The Rap Sheet).

an “unrelentingly dark” new psycho noir novel from New Pulp Press. Flexer is the pseudonym of New Pulp proprietor Jon Basoff.)

an “unrelentingly dark” new psycho noir novel from New Pulp Press. Flexer is the pseudonym of New Pulp proprietor Jon Basoff.)With sleazy cover art and over-the-top titles, Jim Thompson’s books often appeared indistinguishable from all the other cheap paperbacks being churned out in the 1950s by publishers such as Gold Medal and Lion Books. But Thompson, nicknamed the “Dimestore Dostoyevsky,” created some of the most poignant literature of the 20th century. Employing unreliable narrators, a wicked sense of humor, and surrealistic imagery, Thompson helped transform the derided pulp genre into art. His most well-regarded works--The Killer Inside Me (1952), Savage Night (1953), A Hell of a Woman (1954), and Pop. 1280 (1964)--all used the disconcerting technique of casting madmen to narrate his tales (filmmaker Stanley Kubrick called The Killer Inside Me “probably the most chilling and believable first-person story of a criminally warped mind I have ever encountered.”). But it was a little-known 1953 novel called The Criminal that perhaps best showed Thompson’s concern for the disintegration of our collective morality.

The Criminal centers around the heinous murder and rape of a teenage girl named Josie Eddleman. Almost immediately, suspicion surrounds Bob Talbert, a teenage neighbor of the victim and the last person to see her alive. But as the novel weaves towards its ambiguous ending, Bob’s guilt or innocence becomes largely irrelevant. No, the audience never does find out if Bob Talbert is guilty of rape or homicide--although he is certainly guilty of something. But then again, every character in this novel is guilty of something. In fact, despite its title, this book is more a study of the jury than the criminal, a study of collective guilt.

One of the more fascinating elements of Thompson’s writing was his constant experimentation with narration. Unlike most pulp novelists, Thompson eschewed a straightforward telling of his yarns, instead creating narrators who are extraordinary for their unreliability. While Thompson was a gifted storyteller, his major strength comes from his psychological portraits. Motives are rarely what they appear to be. Rare, too, is the character in a Thompson novel who has a moral center; rather, we see men and women who are overwhelmed by their own devious thoughts and uncontrolled passions. In The Criminal, Thompson provides not one, but nine different voices. Each of those voices has his/her own version of the truth, but we as readers soon find it apparent that none of those voices really provides the truth, that perhaps there is no single truth, at least not one without prejudice. It is important to note that Jim Thompson was heavily influenced by William Faulkner, and The Criminal certainly has echoes of Faulkner’s Southern Gothic masterpiece, As I Lay Dying (1930), both in terms of theme and narrative technique. And while perhaps The Criminal doesn’t match the narrative genius of As I Lay Dying, it comes mighty close. Thompson lacked Faulkner’s lyricism and uncanny sense of place, but he matched Faulkner in terms of dark humor and social understanding.

Before Thompson became a fiction writer, he was a journalist, and he shows a healthy amount of cynicism for the profession and how the media can create an alternative reality. The newspaper reporter in this novel, a man named Bill Willis, is able to manipulate the public into figuratively crucifying Bob before any evidence is actually presented. Because Bob is known as a sub-par student and all-around slacker, Willis is able to feast upon the public’s tendency to stereotype, and turn a truant into a murderer.

While The Criminal doesn’t contain the spectacular brutality of some of Thompson’s other works, there is a kind of weary resignation evident throughout its pages. Early in the book, Bob’s father says: “You just rock along, doing the things that you have to, and you get kind of startled sometimes when you stand off and look at yourself. You think, my God, that isn’t me. How did I ever get like that? But you go right ahead, startled or not, hating it or not, because you don’t actually have much to say about it. You’re not moving so much as you are being moved.” And later the D.A’s wife muses: “Isn’t it terrible? You’re just like you always were, the very same person, and suddenly that isn’t good enough anymore.”

Some readers may find the ending of The Criminal a bit disappointing, since there is no tidy resolution. However, that ambiguity is exactly what makes the novel powerful. As the story progresses, we can’t help but sympathize with this boy who has been charged with the crime. In fact, when we actually hear from Bob, he comes across as an upstanding young man and a sympathetic character. But Thompson was fascinated by the sociopaths and their ability to make people believe that they are something other than what they really are. For those of us who read The Killer Inside Me and Pop. 1280, we can’t help but wonder if Bob is, in fact, pulling the wool over our eyes.

In the end, the town and tabloids forget about Josie Eddleman, and Bob Talbert’s guilt or innocence becomes largely irrelevant. Ultimately, all that we are left with is a smörgåsbord of greed and betrayal, creating a Thompsonian view of a universe drenched with moral nihilism.

READ MORE: “The Book You Have to Read: The Grifters, by Jim Thompson,” by Chris Knopf (The Rap Sheet).

Labels:

Books You Have to Read,

Jim Thompson

Friday, November 28, 2008

The Book You Have to Read:

“The Grifters,” by Jim Thompson

(Editor’s note: This is the 33rd installment of our ongoing Friday blog series highlighting great but forgotten books. Choosing today’s novel is Chris Knopf. The creative director at a New England  advertising and public relations agency, Knopf is also the author of three books featuring Sam Acquillo, a former corporate exec turned hard-drinking carpenter and sometime detective on Long Island, New York. His latest Acquillo novel is Head Wounds, which came out earlier this year.)

advertising and public relations agency, Knopf is also the author of three books featuring Sam Acquillo, a former corporate exec turned hard-drinking carpenter and sometime detective on Long Island, New York. His latest Acquillo novel is Head Wounds, which came out earlier this year.)

I know Jim Thompson is a crime writer, though after re-reading one of his books, you wonder. Most of the requisite ingredients are there--guns and blood, cops and criminals, explications on the social habits of the wicked and dispossessed. But you can’t help thinking that Thompson only picked the genre as the most expedient route to his actual goal, which was to delve unblinkingly into the casual depravity of your everyday sociopath.

Of course, The Grifters (originally published in 1963) is first-rate noir, which is where it clearly fits within the contemporary taxonomy of crime fiction. Darkly engrossing and fast-moving, with writing that lacerates when it isn’t being lyrical. It’s a brief trip into the netherworld of the professional con, where fleecing suckers is less an adventure than a routine occupation, complete with its own operating manual--unwritten--and its own lexicon.

The protagonist, Roy Dillon, is a natural at this game. Beguilingly ordinary and unassuming on the outside, the kind of guy everyone likes to talk to, everyone immediately trusts. He’s highly intelligent, resourceful, courteous, and responsible--a paragon of respectability. He’s also utterly devoid of remorse over his chosen profession, and indifferent to the misfortune he bestows upon others.

Then again, you wonder. Roy’s behavior is learned from his mother, Lilly, another citizen of the criminal fringe, who bore Roy when she was barely out of childhood herself. Lilly knew nothing about raising a kid, and could have cared less. In modern terms, you’d say she was a little light on the nurturing instinct. Roy eventually realizes this, and attends to his own survival as best he can, though with a black resentment just a whiff away from abject hatred for his mother.

This is where the two settle until Roy grows into a handsome young man, which Lilly notices, which seems to stimulate her maternal instincts. Though how maternal are they?

Therein lies the true theme of The Grifters. An academic journal might have titled it “A Freudian Study of Oedipal Psycho-Sexual Conflicts Within the Context of Sociopathological Family Dysfunction.” This is what Thompson’s book is really about: the dramatic tension derived from Roy’s sexual confusion about his mother (his carnal love interest is Moira Langtry, an older woman who’s also been living off the grift) and his mother’s unbridled ambition to totally possess her son.

What really makes it interesting is that Roy seems to be, despite himself, drifting toward some vague sense of conventional morality. Just as he cons regular joes out of their cash, a regular joe seems to be conning him into a respectable job--one that would preclude his grifter’s lifestyle. He shows glimmers of conscience after seducing a young, vulnerable woman. As things evolve, the reader is more aware than he is that he’s possibly stumbling into virtue.

As a writer, I’m cursed with attention to style. Thompson reminds me of Henry Miller--gifted, literate, and undisciplined. His prose hurtles along in a voice both naturalistic and poetical, which then suddenly becomes awkward or obtuse. It makes me wonder about his editor, or whether he had one at all. Aside from the casual copy editing, did anyone in the employ of his publisher notice that 80 percent of this book was psychological study and 20 percent was action thriller?

Thompson owes a lot to the pulp writers of his time and before, but he still stands apart. He wrote like a fallen angel, alternately brilliant and profane. Though he had the pulp sympathy for the regular guy, the man on the street. You can hear it in his dialogue, the “Hey, fella, how’a doin’?” rhythms of the American vernacular. Occasionally, the writing has the poise and pitch of the finest literary novelists of Thompson’s era. I sense that he understood his own potential, and was plagued by the fear, justified, that it would never be fully realized.

Interestingly, movie producers are among Thompson’s biggest fans. An amazing number of his novels have been turned into movies, notably The Grifters, The Getaway, The Killer Inside Me, and Pop. 1280, the last of which morphed into a French film called Coup de Torchon. I think the attraction is partly the fresh story lines and tight dialogue, but also the intimacy of Thompson’s descriptions, the cinematic evocations of this flawed, but ultimately satisfying writer.

I often find cult authors to be well-deserving of their anonymity, but Jim Thompson is consistently fun to read, and usually bracing in his harsh, gimlet-eyed view of the world. Or rather, the underworld, populated by drunks, con men, hookers, gamblers, gangsters, and thieves. It feels like these are all people Thompson knows well, that he’s been there, lived the life they live, and thus is merely reporting on a parallel universe of amorality, one respectable people should only visit vicariously from the safety of their reading chairs and comfortable beds.

advertising and public relations agency, Knopf is also the author of three books featuring Sam Acquillo, a former corporate exec turned hard-drinking carpenter and sometime detective on Long Island, New York. His latest Acquillo novel is Head Wounds, which came out earlier this year.)

advertising and public relations agency, Knopf is also the author of three books featuring Sam Acquillo, a former corporate exec turned hard-drinking carpenter and sometime detective on Long Island, New York. His latest Acquillo novel is Head Wounds, which came out earlier this year.)I know Jim Thompson is a crime writer, though after re-reading one of his books, you wonder. Most of the requisite ingredients are there--guns and blood, cops and criminals, explications on the social habits of the wicked and dispossessed. But you can’t help thinking that Thompson only picked the genre as the most expedient route to his actual goal, which was to delve unblinkingly into the casual depravity of your everyday sociopath.

Of course, The Grifters (originally published in 1963) is first-rate noir, which is where it clearly fits within the contemporary taxonomy of crime fiction. Darkly engrossing and fast-moving, with writing that lacerates when it isn’t being lyrical. It’s a brief trip into the netherworld of the professional con, where fleecing suckers is less an adventure than a routine occupation, complete with its own operating manual--unwritten--and its own lexicon.

The protagonist, Roy Dillon, is a natural at this game. Beguilingly ordinary and unassuming on the outside, the kind of guy everyone likes to talk to, everyone immediately trusts. He’s highly intelligent, resourceful, courteous, and responsible--a paragon of respectability. He’s also utterly devoid of remorse over his chosen profession, and indifferent to the misfortune he bestows upon others.

Then again, you wonder. Roy’s behavior is learned from his mother, Lilly, another citizen of the criminal fringe, who bore Roy when she was barely out of childhood herself. Lilly knew nothing about raising a kid, and could have cared less. In modern terms, you’d say she was a little light on the nurturing instinct. Roy eventually realizes this, and attends to his own survival as best he can, though with a black resentment just a whiff away from abject hatred for his mother.

This is where the two settle until Roy grows into a handsome young man, which Lilly notices, which seems to stimulate her maternal instincts. Though how maternal are they?

Therein lies the true theme of The Grifters. An academic journal might have titled it “A Freudian Study of Oedipal Psycho-Sexual Conflicts Within the Context of Sociopathological Family Dysfunction.” This is what Thompson’s book is really about: the dramatic tension derived from Roy’s sexual confusion about his mother (his carnal love interest is Moira Langtry, an older woman who’s also been living off the grift) and his mother’s unbridled ambition to totally possess her son.

What really makes it interesting is that Roy seems to be, despite himself, drifting toward some vague sense of conventional morality. Just as he cons regular joes out of their cash, a regular joe seems to be conning him into a respectable job--one that would preclude his grifter’s lifestyle. He shows glimmers of conscience after seducing a young, vulnerable woman. As things evolve, the reader is more aware than he is that he’s possibly stumbling into virtue.

As a writer, I’m cursed with attention to style. Thompson reminds me of Henry Miller--gifted, literate, and undisciplined. His prose hurtles along in a voice both naturalistic and poetical, which then suddenly becomes awkward or obtuse. It makes me wonder about his editor, or whether he had one at all. Aside from the casual copy editing, did anyone in the employ of his publisher notice that 80 percent of this book was psychological study and 20 percent was action thriller?

Thompson owes a lot to the pulp writers of his time and before, but he still stands apart. He wrote like a fallen angel, alternately brilliant and profane. Though he had the pulp sympathy for the regular guy, the man on the street. You can hear it in his dialogue, the “Hey, fella, how’a doin’?” rhythms of the American vernacular. Occasionally, the writing has the poise and pitch of the finest literary novelists of Thompson’s era. I sense that he understood his own potential, and was plagued by the fear, justified, that it would never be fully realized.

Interestingly, movie producers are among Thompson’s biggest fans. An amazing number of his novels have been turned into movies, notably The Grifters, The Getaway, The Killer Inside Me, and Pop. 1280, the last of which morphed into a French film called Coup de Torchon. I think the attraction is partly the fresh story lines and tight dialogue, but also the intimacy of Thompson’s descriptions, the cinematic evocations of this flawed, but ultimately satisfying writer.

I often find cult authors to be well-deserving of their anonymity, but Jim Thompson is consistently fun to read, and usually bracing in his harsh, gimlet-eyed view of the world. Or rather, the underworld, populated by drunks, con men, hookers, gamblers, gangsters, and thieves. It feels like these are all people Thompson knows well, that he’s been there, lived the life they live, and thus is merely reporting on a parallel universe of amorality, one respectable people should only visit vicariously from the safety of their reading chairs and comfortable beds.

Labels:

Books You Have to Read,

Jim Thompson

Monday, October 30, 2006

A Hell of a Find

Wow, a very long-lost Jim Thompson film treatment called Lunatic at Large? And plans to finally produce a movie from the script that renowned director Stanley Kubrick failed to use before his death in 1999? Where do I get in line for tickets?

Labels:

Jim Thompson

Wednesday, September 27, 2006

Birthday for a Grifter

Jim Thompson, just about the hardest-boiled of them all, was born today back in 1906. Thompson’s books were filled with drifters and grifters, some of them shrewd and sharp, others considerably less so. It is believed that many of his characters had autobiographical components, and Thompson’s life was at times as bleak as many of his creations. He suffered a nervous breakdown at age 19, after already cultivating a life of smoking and drinking. While working as a bellboy at the Hotel Texas in Fort Worth, he made the majority of his money acting as a heroin and marijuana courier for the hotel’s guests.

Jim Thompson, just about the hardest-boiled of them all, was born today back in 1906. Thompson’s books were filled with drifters and grifters, some of them shrewd and sharp, others considerably less so. It is believed that many of his characters had autobiographical components, and Thompson’s life was at times as bleak as many of his creations. He suffered a nervous breakdown at age 19, after already cultivating a life of smoking and drinking. While working as a bellboy at the Hotel Texas in Fort Worth, he made the majority of his money acting as a heroin and marijuana courier for the hotel’s guests.In a career that spanned more than 30 years, Thompson published a string of novels that have come to epitomize both pulp fiction and the allure of noir. He is best known for The Killer Inside Me, The Grifters, and After Dark, My Sweet.

Like many other writers of his generation, Thompson tried his luck in Hollywood. A number of his books were adapted for film, and he also wrote screenplays for motion pictures and scripts for television. He is believed to have written most of the script for Stanley Kubrick’s classic Paths of Glory, but Kubrick’s ego prevented Thompson from receiving the solo writing credit. Toward the end of his life, Thompson was hired to adapt his novel The Getaway, but was dismissed by the film’s star, Steve McQueen, who found Thompson’s treatment too dark. It makes one wonder who McQueen thought he was hiring. Thompson can be seen making a cameo appearance in Farewell, My Lovely, playing Judge Baxter Wilson Grayle.

Thompson died in 1971, having suffered several strokes, aggravated by alcoholism and self-starvation. He was at the time largely forgotten, but since his death, his star has risen. The Grifters was made into a successful film, featuring a script by Donald Westlake and a star turn by a young Annette Bening as the dangerous seductress Myra Langtry. Black Lizard returned many of his novels to print. Thompson was also the subject of a serious biography, Savage Art, by Robert Polito.

Labels:

Birthdays,

Jim Thompson

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)