One could make the same argument when reading hard-boiled or noir novels from the 1930s and ’40s. To many contemporary readers, these novels now read as parodies, the originals that we mistake for copies. I have often found, when teaching from these books, that students approach them through the haze of decades of noir kitsch--the totems of the liquor bottle in the desk drawer, the femme fatale’s entrance--the idiom itself provoking laughter, as if these books were indulging in clichés rather than spawning a rich tradition.

One of the risks, then, in writing noir or hard-boiled fiction today is veering (or plunging) headlong into parody or kitsch. While there might be any number of rewards for readers or viewers in kitsch, its very nature, its ironic distance, forbids access to an elemental pleasure: that of identification, of identifying with the characters on the page. This phenomenon creates a weighty challenge for contemporary writers seeking to produce fresh novels in this tradition. How do you write, say, a hard-boiled detective or heist novel, or a noir couple-on-the-run novel, that does not reiterate or react against the conventions? How can you engage the reader to identify if he or she feels like it’s all a quaint exercise in nostalgia?

The brilliant Hard Case Crime has gone a long way toward answering this question with its rich output of fresh, new novels that speak to the tradition without becoming its slave or its wink-nudge parodist.

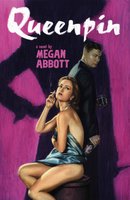

How to manage this balance is tricky. I tried to figure it out when writing Queenpin (due out in June), my effort to write a hard-boiled story in the traditions of the writers I so idolized (Cain, Woolrich, McCoy, Thompson, et al.), but with two women at the center of a story that might, more typically, foreground two men: the veteran mob courier and the protégée learning the ropes. I tried to keep in mind that a primary reason novels like Double Indemnity or They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? stick with us are not the style and the pleasures of the idiom, even as we savor both--it’s the characters. Characters that endure, that hum in our brains. I could listen to Walter Huff whispering his self-delusions in my ear forever. I guess this is because, even if it takes a little while, we can overcome the distance of which Žižek speaks. I think when we read Walter, we want to judge him, which means we’re very close indeed--we want him to wake up to the trap he walks into, and then we realize it’s a trap he set himself.

How to manage this balance is tricky. I tried to figure it out when writing Queenpin (due out in June), my effort to write a hard-boiled story in the traditions of the writers I so idolized (Cain, Woolrich, McCoy, Thompson, et al.), but with two women at the center of a story that might, more typically, foreground two men: the veteran mob courier and the protégée learning the ropes. I tried to keep in mind that a primary reason novels like Double Indemnity or They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? stick with us are not the style and the pleasures of the idiom, even as we savor both--it’s the characters. Characters that endure, that hum in our brains. I could listen to Walter Huff whispering his self-delusions in my ear forever. I guess this is because, even if it takes a little while, we can overcome the distance of which Žižek speaks. I think when we read Walter, we want to judge him, which means we’re very close indeed--we want him to wake up to the trap he walks into, and then we realize it’s a trap he set himself.

No comments:

Post a Comment