I’ve come to worry about taking such extended excursions abroad--not because of airplane hazards or terrorist attacks, because something always seems to go wrong back home during my absence. The last time my wife and I ventured across the Atlantic, the U.S. military’s Abu Ghraib prisoner torture scandal exploded, splashing photographs of naked, leashed, and hooded Iraqi detainees all over the London tabloids and Paris TV news programs. The news wasn’t quite so horrific this time around, but it was impossible, even in Spain and Portugal, to miss reports about a spy agency study showing that George W. Bush’s Iraq war has worsened global terrorist threats, not reduced them; word that U.S. Representative Mark Foley (R-Florida) sent sexually explicit e-notes to teenage male congressional pages; and, of course, coverage of the death of Anna Nicole Smith’s 20-year-old son and the ensuing controversy over her baby daughter’s paternity. (The Euro tabs just love out-of-control celebrities, don’t they?)

I’ve come to worry about taking such extended excursions abroad--not because of airplane hazards or terrorist attacks, because something always seems to go wrong back home during my absence. The last time my wife and I ventured across the Atlantic, the U.S. military’s Abu Ghraib prisoner torture scandal exploded, splashing photographs of naked, leashed, and hooded Iraqi detainees all over the London tabloids and Paris TV news programs. The news wasn’t quite so horrific this time around, but it was impossible, even in Spain and Portugal, to miss reports about a spy agency study showing that George W. Bush’s Iraq war has worsened global terrorist threats, not reduced them; word that U.S. Representative Mark Foley (R-Florida) sent sexually explicit e-notes to teenage male congressional pages; and, of course, coverage of the death of Anna Nicole Smith’s 20-year-old son and the ensuing controversy over her baby daughter’s paternity. (The Euro tabs just love out-of-control celebrities, don’t they?)Fortunately, there were other things beyond the news to occupy my time and attention.

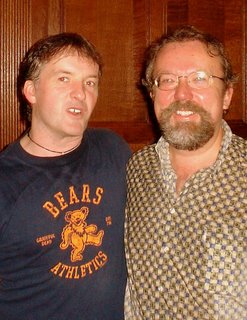

Just a day after touching down in London, we attended a debut celebration for John Connolly’s newest, non-series novel, The Book of Lost Things, thrown by his UK publisher, Hodder & Stoughton. It was held at a venue called Staple Inn Hall, a Tudor-fronted edifice on High Holborn that is much easier to describe than locate. Our West African cabbie searched for a good 20 minutes before finally emptying us--in the cascading rain--across the street and down the block. By the time I arrived at the party, I looked like a rat somebody had tried--not too successfully--to flush down a toilet. (That’s me above on the right, with Connolly.) However, the author, his publicists, and January contributor Ali Karim, who’d arranged our invitation to this fête, all did their damndest to make us welcome. As did Shots editor Mike Stotter and stand-up comic-turned-author Mark Billingham (Buried), both of whom I first met two years ago during another London book launch, that one for Michael Marshall’s The Lonely Dead. Because London is Britain’s largest city (some UK critics refer to it as another country altogether), book events held there tend to be substantial and collegial, not unlike what you find in Manhattan. And thanks to folks like Ali, who’s an enthusiastic raconteur in addition to being a most gracious host, we continued the festivities well after the Staple Inn had gone dark, ending up in a pub that was pouring pints long before the United States was a twinkle in the Founding Fathers’ eyes.

It’s impossible for me to visit Britain’s capital without making the rounds of its multitudinous bookshops. And even knowing that I would have to carry whatever I purchased so early in our adventure all across Europe, I just couldn’t stop pulling out my credit card. Calls on several of my favorite Charing Cross stores (Foyles, Murder One, and Goldsboro Books) netted me an armload of weighty new titles, including a pair of historical thrillers, The Interpretation of Murder, by Jed Rubenfeld, and Critique of Criminal Reason, by Michael Gregorio. On top of the advanced reader copies I had packed clear across the Atlantic (The Hidden Assassins, by Robert Wilson, and Steve Hamilton’s A Stolen Season), these additions left me fairly confident that I wouldn’t run out of reading matter--at least not until we passed through London again on our way back to Seattle.

From the UK, we flew to see friends in the Dutch city of Utrecht, just in time to help celebrate their younger daughter’s 14th birthday. Then it was on to Barcelona, Spain. I’d been on the Iberian Peninsula once before, but had then confined my travels to Madrid and Toledo, in the nation’s midsection. Barcelona turned out to be both more beautiful and more bustling than I had expected, a Mediterranean-side city filled with leaping fountains, narrow side avenues opening suddenly into sunlit plazas, and street performers peppered along La Rambla--downtown’s lengthy pedestrian mall--those entertainers dressed up variously as Egyptian queens, skeletal bicyclists, and horny devils ready to perform for anybody who’ll flip a few coins into their cans. (Needless to say, I contributed a jingling wealth of euros to these sidewalk amusements.)

From the UK, we flew to see friends in the Dutch city of Utrecht, just in time to help celebrate their younger daughter’s 14th birthday. Then it was on to Barcelona, Spain. I’d been on the Iberian Peninsula once before, but had then confined my travels to Madrid and Toledo, in the nation’s midsection. Barcelona turned out to be both more beautiful and more bustling than I had expected, a Mediterranean-side city filled with leaping fountains, narrow side avenues opening suddenly into sunlit plazas, and street performers peppered along La Rambla--downtown’s lengthy pedestrian mall--those entertainers dressed up variously as Egyptian queens, skeletal bicyclists, and horny devils ready to perform for anybody who’ll flip a few coins into their cans. (Needless to say, I contributed a jingling wealth of euros to these sidewalk amusements.)Although it’s centuries old, Barcelona feels vital and modern, capturing one’s imagination and attention with its early 20th-century--yet somehow timeless--landmarks by Catalan designer Antonio Gaudí (best known for his as-yet-unfinished Sagrada Familia church, shown above at left), and its superfluity of stylishly attired young women--slender, dark-maned, and bursting with sensuality enough to make a priest rethink his celebate ways. I felt right at home in Barcelona, my only regret being that there weren’t many in the way of English-language bookstores; I’d been hoping to expand my familiarity with Spanish crime writers beyond the likes of Manuel Vázquez Montalbán (An Olympic Death), José Carlos Somoza (The Athenian Murders), and Arturo Pérez-Reverte (The Club Dumas). But no such luck this time out.

Equally scarce were English-translated titles in Seville, our next stop, though by then, it didn’t seem to matter quite so much. Located in the country’s southern quarter, Seville is a once-important seaport (Ferdinand Magellan acquired the ships he needed for his circumnavigation of the globe here), much of its architecture reminding visitors of this burg’s long-ago domination by the Moors.

My curiosity about Seville had been sparked by reading Robert Wilson’s The Blind Man of Seville, one of January’s favorite books of 2003. I had imagined a peaceful small town resplendent with flowers and other decorative foliage, catering to tourists with its flamenco dances and orange trees, but also a siesta sort of place that existed primarily as a museum piece. However, Seville appears less encumbered than enlivened by its manifest history--its largest-of-them-all Catholic cathedral, its grandiose but graceful Alcázar (royal palace), and its striking Plaza de España, a crescent-shaped expression of Moorish Revival architecture left over from the 1929 Ibero-American Exposition (see photo at right). You can easily become disoriented amid a maze of twisting back streets, wishing you’d dropped bread crumbs along the way in order to ease your homeward trek. Yet in getting lost, you’ll probably find a corner café where the waitresses will let you sit all day long without the petty annoyance of a bill, or stumble across some Spanish guitarist in a shady park who’s patiently massaging the kinks from his latest piece and doesn’t mind if you sit and listen for a hour--or an afternoon. It’s unlikely I’ll forget the pocket-edition bar we happened across while looking for the riverfront, and the stocky guy in a black suit (surprisingly, not sweat-soaked in Seville’s 80-plus-degree fall weather) who ushered us in to watch an impromptu flamenco performance by several neighborhood gents, old and young. “You ain’t goin’ to see this sort of show in any fancy fuckin’ flamenco club,” he insisted in an English heavily flavored by his 15 years spent in New York City.

My curiosity about Seville had been sparked by reading Robert Wilson’s The Blind Man of Seville, one of January’s favorite books of 2003. I had imagined a peaceful small town resplendent with flowers and other decorative foliage, catering to tourists with its flamenco dances and orange trees, but also a siesta sort of place that existed primarily as a museum piece. However, Seville appears less encumbered than enlivened by its manifest history--its largest-of-them-all Catholic cathedral, its grandiose but graceful Alcázar (royal palace), and its striking Plaza de España, a crescent-shaped expression of Moorish Revival architecture left over from the 1929 Ibero-American Exposition (see photo at right). You can easily become disoriented amid a maze of twisting back streets, wishing you’d dropped bread crumbs along the way in order to ease your homeward trek. Yet in getting lost, you’ll probably find a corner café where the waitresses will let you sit all day long without the petty annoyance of a bill, or stumble across some Spanish guitarist in a shady park who’s patiently massaging the kinks from his latest piece and doesn’t mind if you sit and listen for a hour--or an afternoon. It’s unlikely I’ll forget the pocket-edition bar we happened across while looking for the riverfront, and the stocky guy in a black suit (surprisingly, not sweat-soaked in Seville’s 80-plus-degree fall weather) who ushered us in to watch an impromptu flamenco performance by several neighborhood gents, old and young. “You ain’t goin’ to see this sort of show in any fancy fuckin’ flamenco club,” he insisted in an English heavily flavored by his 15 years spent in New York City.If Barcelona is a city to stir the heart and mind, Seville is a town to stir the senses, inviting one to linger in manicured commons and cafés, to breathe in the fragrances from tapas bars or of a lover’s perfume, to silently observe passersby or enjoy a good book.

But it’s Lisbon, Portugal, that I think makes the finest setting for a crime novel. Mainland Europe’s westernmost capital--and our final destination on this trip--is reportedly less touristed than the continent’s other big cities, and there are some urban residential sections that look more Third World than First (yet where folks are still somehow able to decorate their balconies with TV dish antennae). It lays claim to a wonderful history--Roman and Moorish, but also imperial and disastrous and dictatorial--from which to draw storytelling references, and the architecture in this hilly metropolis runs the gamut from whimsical to grandiose, with cramped-looking Smart cars and colorful, bell-clanging trolleys wending their way throughout. I can easily imagine clandestine money exchanges taking place in the Praça do Comércio, or Commerce Square (photographed below, left), which fronts the Tagus River. A down-at-heel private eye would be right at home confronting a suspect aboard the Elevador de Santa Justa, a richly patterned 1902 neo-Gothic lift designed by Raoul Mesnier du Ponsard, a French apprentice to Gustave Eiffel. And if there’s to be a foot chase after a murderer, let it be made through the Castle of São Jorge, a crenelated pile recaptured from the Moors in the 12th century, extensively reconstructed in the 1940s, and still looming over Lisbon from its highest point. Automobile chases through Lisbon’s capacious downtown thoroughfares or narrow, cobbled side streets might be captivating.

Surprisingly, though, there seems to be little crime fiction written in English and set in Portugal’s largest, richest urban center. Brit Robert Wilson’s Gold Dagger Award-winning A Small Death in Lisbon (1999) takes place partly there, as does his subsequent novel, The Company of Strangers (2001). By it’s name, it is rather obvious that Richard Zimler’s The Last Kabbalist of Lisbon (1998), a mystery with religious overtones, is set on these same banks of the Tagus. But I’m at a loss to come up with any other noteworthy criminal tales boasting a Lisbon backdrop. If anybody out there knows of additional titles--particularly historical ones--please let me know.

Surprisingly, though, there seems to be little crime fiction written in English and set in Portugal’s largest, richest urban center. Brit Robert Wilson’s Gold Dagger Award-winning A Small Death in Lisbon (1999) takes place partly there, as does his subsequent novel, The Company of Strangers (2001). By it’s name, it is rather obvious that Richard Zimler’s The Last Kabbalist of Lisbon (1998), a mystery with religious overtones, is set on these same banks of the Tagus. But I’m at a loss to come up with any other noteworthy criminal tales boasting a Lisbon backdrop. If anybody out there knows of additional titles--particularly historical ones--please let me know.We spent most of a week around Lisbon, admiring its museums and churches and immense public squares, training out to see at least one of its beachside neighbors (Cascais, a former fishing village founded in the 12th century), and visiting the monumental relics at Belém, an adjacent parish from which the Portuguese explorers of yore embarked on their voyages of discovery. (One of the most recognizable symbols of Lisbon can be found in that latter location: Belém Tower, a sumptuously wrought former defensive installation that sits smack dab in the Tagus.)

Before we were ready, however, our holiday was over. So, bearing an armload of books that made it rather difficult to deal with other luggage (hey, a guy’s gotta have his priorities, right?), I set off once more for London’s Heathrow Airport, where I bought yet another book, this one to keep me occupied during our nine-hour connecting flight back to the States: Under Orders, the 39th novel from British jockey-turned-author Dick Francis. It had been many years since I’d read a Francis story (the last one previous, I think, having been 1987’s Hot Money), yet before boarding the plane home to Seattle, I felt the need for something, well, comfortable. Under Orders, the third novel (after Odds Against and Whip Hand) to star P.I. and ex-jockey Sid Halley, seemed just the ticket. Even before we taxied out to the runway, I was blissfully lost in Francis’ tale of horse-race fixing, off-track betting, duplicity, and murder. Somewhere over Greenland, my eyes finally shut.

2 comments:

Interesting read.

Yes,

It was a super [if somewhat wet] evening in London - but great fun to see you again.

As usual it was difficult to shut me up, but then again it was a great night

Ali

Post a Comment