(Editor’s note: It was 70 years ago today that an audacious burglary took place on France’s Côte d'Azur, inspiring author David Dodge to pen one of the best-known crime-caper novels of the 20th century. In the essay below, Randal S. Brandt, a librarian at the University of California, Berkeley’s Bancroft Library and creator of the Web’s A David Dodge Companion, recounts the circumstances of that robbery and the man responsible for its deft execution.)

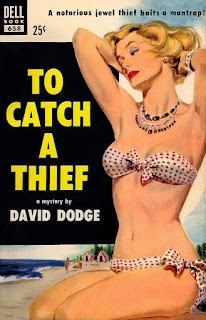

Alfred Hitchcock’s romantic thriller To Catch a Thief was released by Paramount Pictures in August 1955. While generally acknowledged as being one of the lighter-weight films directed by the “Master of Suspense,” it contains many of the hallmarks for which Hitchcock is rightfully recognized: an innocent man falsely accused of crimes he did not commit; a cool blonde with mysterious motives; a setting shot through with glamour and romance; and a suspense-filled plot involving a race against time—in this case, an ex-jewel thief (played by Cary Grant) who has to catch a copycat pulling off a series of daring heists on the French Riviera in order to prove his own innocence and clear his name. As was common throughout Hitchcock’s career, this film was adapted from a previously published work.

To Catch a Thief, the 1952 novel upon which the screenplay was based, tells the story of John Robie, an American expatriate who is trying to live a quiet life in a villa, which he audaciously names Villa des Bijoux (Villa of the Jewels), in the South of France. Before World War II, Robie had put his acrobatic training to use as a jewel thief operating on the Côte d’Azur and was nicknamed Le Chat (The Cat) by the French press for his gravity-defying ability to soundlessly enter and exit hotel rooms and apartments of his wealthy victims. He worked alone and “was never known to employ violence or carry a weapon more dangerous than a glass cutter.” Eventually, he was arrested and sentenced to 20 years in a French prison. When the Germans occupied France during the war, they emptied the jails. Robie, along with his cellmates, went into the maquis, the French underground, and fought against the Germans. In exchange for their service to France, the ex-prisoners were extended an unofficial amnesty for their

crimes—provided they stay out of trouble. Now a new thief is at work on the Riviera, using Robie’s exact methods, and the police are convinced that Le Chat is back in business. So, Robie determines to catch the thief himself.

crimes—provided they stay out of trouble. Now a new thief is at work on the Riviera, using Robie’s exact methods, and the police are convinced that Le Chat is back in business. So, Robie determines to catch the thief himself.The novel was written by American mystery writer David Dodge (1910-1974) while he was living with his wife, Elva, and pre-teen daughter, Kendal, in the South of France. Even before being given the Hitchcock treatment, it was destined to become Dodge’s most celebrated—and successful—book. In his 1962 travel memoir, The Rich Man’s Guide to the Riviera, Dodge referred to the inspiration for the story as a “stroke of luck that fell to earth on the Côte d’Azur,” and he said that once he had the story in his mind, it was “the easiest eighty thousand words ever put together. The book practically wrote itself.”

David Dodge arrived in France with his family in the spring of 1950, where they rented a house on a hill above Golfe-Juan, near Cannes. By agreeing to also act as groundskeeper and attempt to tame the neglected, overgrown garden, Dodge was able to install his family in a furnished villa with a view of the Mediterranean and employ an elderly, partially-deaf local woman named Germaine to cook and keep house. The Dodges’ modest villa was named Noël Fleuri and shared a garden wall with a much grander villa occupied by a “millionaire industrialist” that was the scene of frequent, glittering parties with glamorous guest lists. Shortly after their arrival, David and Elva enrolled Kendal in a girls’ boarding school at Cannes and left for Italy, where David had a freelance assignment for Holiday magazine. The very night they departed, the villa next door was struck by an acrobatic cat burglar while the guests were dining on the terrace. Dodge recounted the story in The Rich Man’s Guide to the Riviera:

Simultaneously with our departure, apparently to the hour and minute as far as anyone could determine, jewelry purporting to be worth a quarter of a million dollars left the wealthy industrialist’s home next door. The true value of the heist was never, as far as the record goes, accurately determined ... In all events a substantial haul of glittery valuables disappeared from the bedrooms of the industrialist’s wife and her guests the night we, the next-door neighbors, left unannounced for foreign parts. Entrance to the scene of the crime appeared to have been made by a muscular thief who had swarmed three floors up and down a drainpipe, or some such acrobatic exercise.Inevitably, the mysterious American living next door, who vanished simultaneously with the jewels, became the prime suspect in the robbery. When questioned by the police, Germaine, who had a stubborn peasant’s natural dislike of the flics, did Dodge no favors when she refused to cooperate and answer questions about her employers, only adding to the substantial dossier of circumstantial evidence against him. As Dodge later noted, had he “been on hand to demonstrate the comic potentialities of a scenario calling for a middle-aged pear-shaped husband and father to shinny three floors up a drainpipe and back down again, the case against [him] would have collapsed in brays of appreciative French laughter.”

Eventually, when the police discovered that the Dodges had left a daughter behind in boarding school, the case did collapse. By the time David and Elva returned to Golfe-Juan, all the excitement had died down and Dodge was no longer on the “most wanted” list, because the actual thief was securely behind bars.

The crook, a good-looking young Italian porch-climber named Dario Sambucco doing business under the picaresque alias of Dante Spada, was by then in the can. He had pulled off several other successful acrobatic harvesting operations, but made the mistake of opening negotiations with a fence in Lyon who peached on him when they disagreed about a price for the stuff. On my own, I would never have thought of projecting myself into Dante’s rubber-soled shoes, or putting him in mine. We were simply not reconcilable people in reality. Aided, however, by the fertile fancy of others, I saw in the combination a fiction which was, for once, so much stranger than truth that it cried out to be immortalized between hard covers.And thus were John Robie and the plot of To Catch a Thief born.

But who was Dante Spada?

There is very little consensus on the biographical details of Dario Sambucco’s life, other than that he was Italian. After his arrest in 1950, Sambucco first insisted to the police that his name was Mario Noiret and that he was an itinerant antiques dealer, traveling around the French countryside on a motorized bicycle looking for deals in second-hand furniture. When confronted with armfuls of evidence he was accused of stealing, along with the detention of his girlfriend, however, he confessed to the robberies and claimed that his name was Dante Spada and that he had been born in Padua, the son of a pastry maker, on January 10, 1927. The Paris newspaper Le Monde reported that those details had not been confirmed by Italian officials, and said police speculated that he might have been a militant fascist youth under Prime Minister Benito Mussolini, and that he was attempting to escape Italian justice by changing his name. Italian newspapers reported that the culprit was born on May 5, 1928; but the Journal de Monaco, in publicizing his sentencing in the Tribunal Criminel de Monaco

in 1954, recorded that he was instead born May 3, 1929, in Codroipo, Italy, which is consistent with later references to his age and hometown.

in 1954, recorded that he was instead born May 3, 1929, in Codroipo, Italy, which is consistent with later references to his age and hometown.(Left) The elusive Dante Spada

Dante Spada’s criminal career was documented locally in the pages of Nice-Matin, the daily regional French paper covering Nice and the Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur region (as Dodge noted, “The French press were crazy about him”), which emphasized his good looks by comparing him to French film star Jean Marais. In addition, the newspapers dubbed him Tarzan des campings (Tarzan of the Campgrounds) in reference to his acrobatic skills. His story was exported to the United States, where the press also clearly went “crazy” about him, picking up on his colorful nicknames and breathlessly reporting on the exploits of “Tarzan of the Côte d’Azur” or “Tarzan of the Riviera,” or sometimes even the “Phantom of the Riviera.”

Spada’s criminal escapades began in 1947 with a robbery in Milan, Italy, that he committed with an accomplice. In 1948 he hitchhiked to the South of France, where he was stopped at the border and had all of his money confiscated, but was allowed to continue. After a few clumsy robberies in Cannes, he was picked up by police and sentenced to two years in prison in Marseille. A model prisoner, Spada was released after eight months for good behavior. He then went briefly to Switzerland, where he burglarized an apartment house and netted about $2,000 worth of jewels.

Upon his return to France, his first purchase was a fake identity card in the name of Mario Noiret. He also acquired a motorbike, a camping license from the Touring Club of France, a nylon tent, and other outdoor gear. In order to keep out of sight of the police and others who might recognize him, he hid in the tourist camps outside towns and villages. Spada was reported to have enjoyed living out of doors, where he trained strenuously between jobs by swimming, running, and especially—given his career choice—climbing trees. The New York Daily News reported that “he could go up a tree trunk like a Polynesian after coconuts.” It was this arboreal ability that later led to those many “Tarzan” epithets. While living at Camp des Maurettes in April 1950, Dante met a beautiful young woman named Jeannette and fell madly in love. Jeannette’s last name was never recorded, but she was a divorcée with a 3-year old child, whose parents lived in Lyon. They became engaged and planned to marry the following September.

Nice-Matin reported on 14 separate suspected burglaries committed by Dante Spada on the Côte d’Azur and on the Côte Basque (Biarritz) during the spring and summer of 1950. The most celebrated theft, by far, took place on August 5, 1950, at the Villa Le Roc in Golfe-Juan during a party given by American hostess Rosita Winston who, with her husband, New York property magnate Norman K. Winston, was installed in the villa for the season. Sharing the garden wall with Le Roc was Noël Fleuri, where the Dodges were in residence. In addition to netting Spada a significant haul, the list of victims read like a veritable “who’s who” of the Riviera and included gossip columnist Elsa Maxwell and world-famous fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli. The New York Daily News gave a thrilling account of the heist:

There were two convenient telegraph poles. One of them got him over the railroad’s fence and down onto the tracks. He swarmed up the other in his rubber-soled shoes to the top of the villa’s wall. There he saw a window about five feet away. He jumped across the breach, caught himself and climbed to the roof.Finally casting aside their initial, misguided suspicion of David Dodge, the police turned their attention to Dante Spada, after finding a footprint on the top of a wall following a burglary a few nights later at the Villa Eldee, in Cannes. The Eldee job was one of the strangest—and most opportunistic—escapades on Spada’s rap sheet. In the wake of his successful heist at Le Roc, Spada took Jeannette to Cannes to see a film at Cinema Rex. When the power failed (apparently a common problem at the time), leaving the moviegoers sitting in the dark, Spada claimed he had a headache and needed some fresh air. He told Jeannette to stay in the theater, that he would be back shortly. He took a walk along the Croisette to the Villa Eldee, home of Louis Dreyfus, a former provincial senator, where a dinner party was in progress. He climbed a tree to gain access over the wall, and within minutes had lifted two million francs worth of jewelry. Half an hour later he was back at the movie with Jeannette.

He first entered the room of Mr. and Mrs. Rodman de Heeren … He opened a jewel box on the dressing table with his penknife. (He never carried any weapons or burglar tools.) Among the jewels he got there was a necklace with a diamond pendant at $25,000 to $50,000.

He moved on to [Schiaparelli’s] room where he took, among other things, the Great Bear [a custom piece designed for her by Cartier]. In Mrs. Winston’s room he found the safe locked and passed along, as he is not a cracksman. Next, the Gates’ room ...

Then he left the place the same way he had entered.

(Above) The “Phantom of the Riviera” drew attention worldwide, thanks to newspaper stories like this one that appeared in the Minneapolis Sunday Tribune on August 24, 1952.

(Above) The “Phantom of the Riviera” drew attention worldwide, thanks to newspaper stories like this one that appeared in the Minneapolis Sunday Tribune on August 24, 1952.Up until this point, the police thought the robberies were inside jobs, but the footprint that Spada inadvertently left on the wall at Eldee on his way out suggested that they were dealing, rather, with a “mountain climber.” An inspector with the Cannes police, who had investigated Spada’s work in 1948, knew he had been released from the Marseille jail. A fence with whom Spada had been negotiating the sale of a bag of gems soon identified a picture of him as Mario Noiret, and the police quickly learned that an antiques dealer named Noiret frequented the camps. On August 25, 1950, he was taken into custody by the police outside of Nice.

Spada confessed to 12 burglaries in France and Switzerland, including the robbery at Villa Le Roc. He was motivated to confess when Jeannette was also arrested. It seems likely that she had no idea of his profession until she was picked up by the police. After his arrest, Spada revealed a romantic motive to his crimes: “I intended to reach the 100-million [franc] mark, then settle down as an honest man and marry the girl I love.”

The romance, though, was not destined to last. After initially pledging to stick with him, and reported as being pregnant, Jeannette disappears from Dante Spada’s story. She must have decided that a confessed thief was not the kind of man she wanted for herself or her child. Spada was finally prosecuted for his crimes in February 1953. During the trial, a newspaper in Melbourne, Australia, The Argus, gave an account of his methods:

A burglar climbed trees for two hours a day as rehearsal for a 100-million franc haul ... To get into the Villa Le Roc, at Golfe-Juan, on the Riviera—where Madame Schiaparelli was a guest—“Tarzan” Spada scaled a telephone pole, a wall, and the side of the villa. During the day, Spada acquired a sun tan. In the evening he dressed with care in a white evening suit, black glacé shoes—but with crepe soles. In his hip pocket he carried a chamois leather case with burglar kit and a pair of rubber gloves.On February 27, 1953, Dante Spada was sentenced in Nice to eight years in prison.

His actual stay behind bars was short, however. After his conviction, Spada was extradited to Monaco to face additional charges for a job he had pulled in Monte Carlo on May 27, 1950. On August 15, 1953, he and another prisoner escaped by sawing through the bars of their cell and taking two pistols from the guards. As reported in the press, “French police now consider the move an ‘oversight.’ The Monaco prison is a small, four cell affair more noted for its hospitality than its security.” Spada then fled France for Italy. He was suspected of committing several burglaries in the ensuing months, including a high-profile heist of Hollywood movie mogul Jack Warner’s villa, Aujourd’hui, in Antibes on September 2, 1953. More likely, he was lying low in Italy at the time. He was finally re-arrested in Genoa on November 2, 1953.

This time the police made sure they not only got their man, but that they held onto him, too. In June 1954, Dante Spada—by now more commonly known by his real name, Dario Sambucco—was sentenced to 30 years by the Tribunal Criminel de Monaco. Shortly, thereafter, he was extradited to Milan to face charges stemming from his 1947 robberies. It was there, while recounting his life story to the newspapers, where word reached him that famed director Alfred Hitchcock was in the South of France making a film chronicling the exploits of an acrobatic cat burglar. On July 14, 1954, the Milanese newspaper Corriere della sera reported that Spada had instructed his attorneys to block production of To Catch a Thief. Dodge recounted this angle of the story:

Dante Spada was the first to scream. Until then he had been the epitome of good manners. Everybody liked him, even the cops and his victims, once they had got know him … [W]hile writing his memoirs for the newspapers, he learned that his life story had already been written up for him, and called for justice in the courts.Dodge’s claim to underworld connections is likely an exaggeration (his daughter, Kendal, later wrote that he was the most scrupulously honest man she had ever known). But the copyright laws were, indeed, on Dodge’s side. He recalled in a 1966 Holiday article, that Spada “dropped the complaint when his lawyers explained that a thief can’t copyright his methods of thievery.”

Nothing came of it. It wasn’t any more his life story than it was my own, in fact, a lot less so. I let him know, through a mutual connection in the Marseille underworld, that the copyright laws were on my side, not his, and that if he weren’t careful about what he put into his memoirs somebody might very well countersue for plagiarism.

The Dante Spada story was not quite over yet, though. In 1955, he managed yet another jail break, this time from a prison in Naples. This freedom was likely short-lived, as he was suffering from severe arthritis and using a pair of crutches at the time. Somehow, he managed to simply hobble away from his guards during a medical treatment. A record of his recapture has not yet been located; but in 1972, newspapers detailed that he was ailing and that his widowed mother was campaigning to have his sentence commuted. “It’s not fair,” she reportedly said, “that murderers and rapists go free after a few years while my Dario, who just stole a few million in jewels, is dying in prison like a dog.”

(Above) Elva, David, and Kendal Dodge at the ceremony honoring David as a Chevalier de l’Ordre du Mérite Touristique.

(Above) Elva, David, and Kendal Dodge at the ceremony honoring David as a Chevalier de l’Ordre du Mérite Touristique.The story of Dante Spada is remarkable for how widely it was spread around the world. Newspapers across North America and Europe thrilled their readers with accounts of his burglaries, captures, trials, and escapes. No doubt the fact that he chose Elsa Schiaparelli as one of his victims contributed to his widespread appeal. Schiaparelli, herself, added a bizarre twist to the story. When police were called to the Villa Le Roc following the August 1950 burglary, guests gave detailed reports of the items that were missing. Two weeks later, Schiaparelli was detained by plainclothes detectives at the airport as she was about to board a plane for Tunis, in North Africa. Some of the jewels she had reported stolen were found in her luggage; also there was $1,485 in U.S. dollars that she had failed to declare. In her 1954 autobiography, Shocking Life, Schiaparelli claimed she’d unexpectedly discovered two tiny clips that she had reported missing on her dressing table at the villa, and that she had informed the entire household of her find. The Winstons, however, urged her not to report it, as doing so would just bring the police back to the villa for more unwelcome attention. Schiaparelli was eventually released without being charged—although she had to pay a fine for the undeclared currency. Of course, the press again went “crazy,” with news of her embarrassing detention spreading like wildfire. Upon meeting with the local chief of police the next day, she was told that the detectives had been acting on a tip from someone at the villa. Did it really happen the way she described? Or was she trying to take advantage of the situation to scam her insurers? An unsolved mystery in the Dante Spada saga.

When an author has the right inspiration, the writing comes easily. From the robbery at Villa Le Roc on August 5, 1950, until the publication of To Catch a Thief on January 2, 1952, less than a year and a half had elapsed—the easiest 80,000 words, indeed. Dante Spada clearly was the right inspiration for David Dodge. “Le Chat … came out a kind of mixture of Cary Grant, Mister Universe, Dante Spada and the original suspect,” he explained. Despite the ease with which his story emerged, Dodge had only modest hopes for it. “It was, as it seemed, another potboiler that just might go as far as the paperback reprints. But Le Chat caught on …”

The novel, and its subsequent adaptation to the silver screen, was just the start of a lifelong love affair between Dodge and La Belle France. More novels with French settings and numerous articles for Holiday and other periodicals extolling the beauty and charm of the country followed, ultimately resulting in Dodge being appointed Chevalier de l’Ordre du Mérite Touristique for his contributions to French tourism. He was given a medal on a ribbon and a citation proclaiming him le plus grand agent americain de publicité de la Côte d’Azur. For most people, being accused of a crime you did not commit would be a horrific experience. For David Dodge, it was one of the luckiest things that ever happened to him.

Hitchcock’s cinematic version of To Catch a Thief debuted in Los Angeles on August 3, 1955—65 years ago this week.

* * *

David Dodge’s To Catch a Thief is available from Bruin Books. For more details about that novel’s adaptation by Alfred Hitchcock, check out Mr. Dodge, Mr. Hitchcock, and the French Riviera, by Jean Buchanan, available from Amazon as a Kindle Single or from Audible.

4 comments:

This was most excellent! I wonder, was the TV series "It Takes a Thief" based on the book/film? I loved that show and of course this film.

Regarding "It Takes a Thief": The short answer is No, the TV series was not based on either the novel or the film. There is a long answer, but that will have to wait for another day...

Love the book, love the movie. Great piece. Thank you.

Fascinating background on the the film and the book. Another fine piece by Randal Brandt!

Post a Comment